[NA PRODAJU / FOR SALE]

o

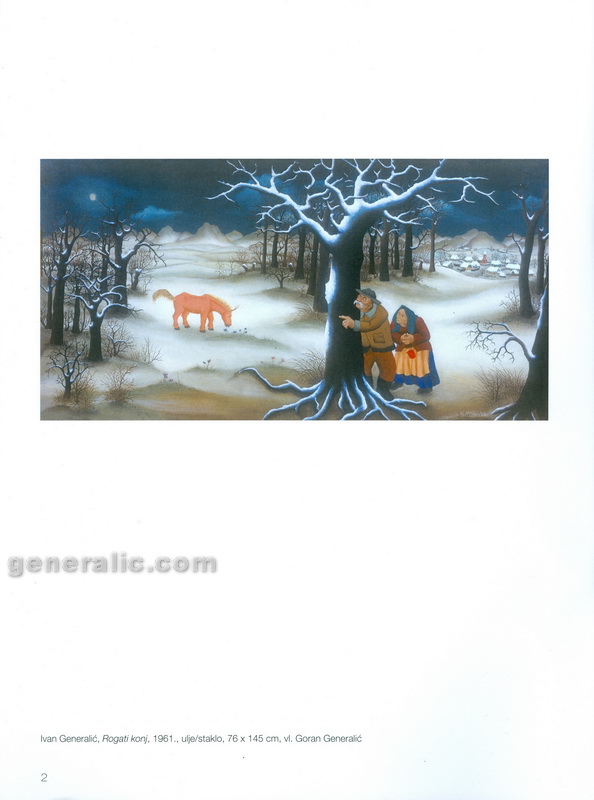

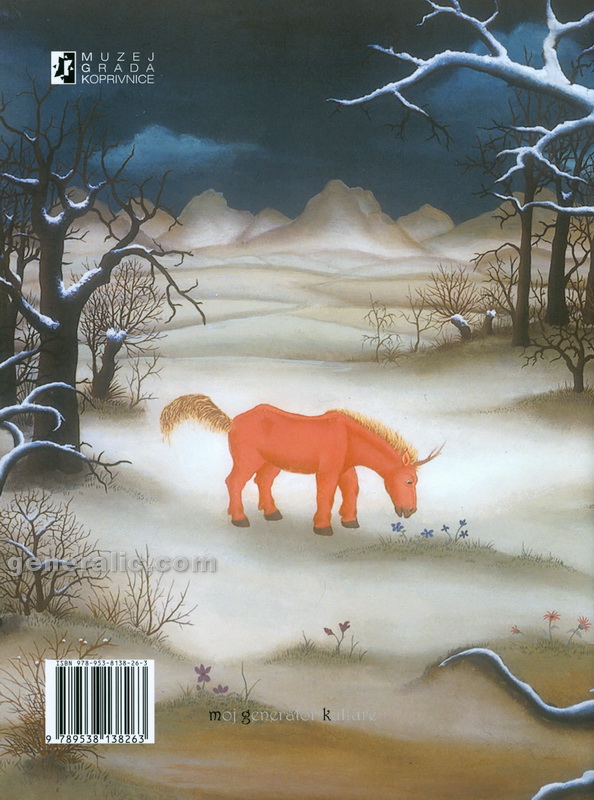

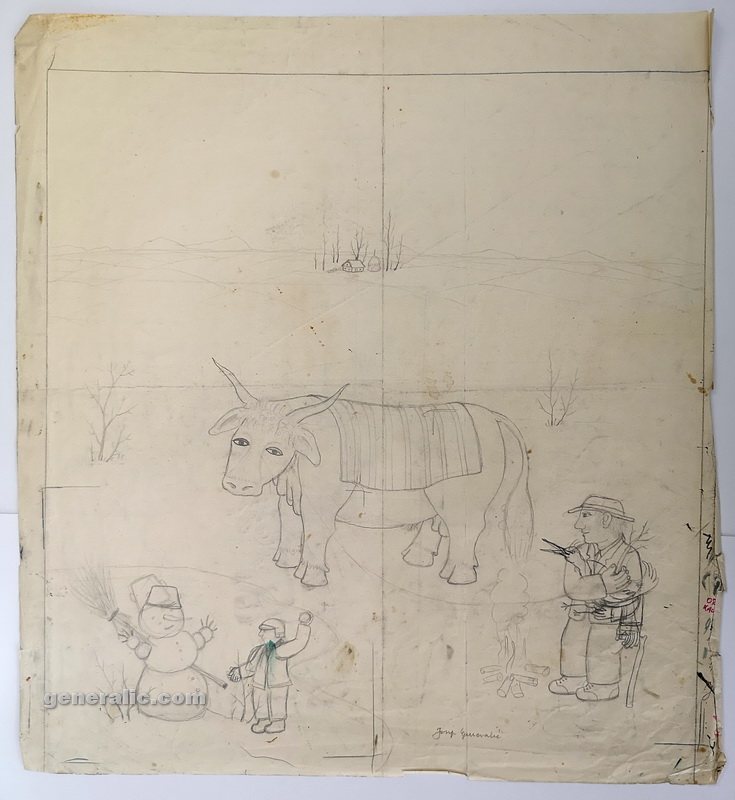

Ivan Generalić, “Rogati konj” (The Unicorn)

- Ivan Generalić, 1961, Rogati konj (The Unicorn), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 76×145 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

- (HR) Djelo Ivana Generalića “Rogati konj“, zaštićeno je kao pokretni spomenik kulture Republike Hrvatske rješenjem Regionalnog zavoda za zaštitu spomenika kulture u Zagrebu, br: 02-748/1-74. od 18. studenog 1974. godine i upisano u Registar pokretnih spomenika kulture Regionalnog zavoda za zaštitu spomenika kulture u Zagrebu pod brojem RZG-138.

Djelo “Rogati konj” Ivana Generalića, ulje na sekuritu, 76×145 cm, sign. D.d. I.Gen. 1961, jedno je od najkvalitetnijih Generalićevih djela iz 60-ih godina, izuzetno po kolorističkoj smionosti uvjetovanoj temom iz narodne priče. Djelo posjeduje sve karakteristike Generalićeva osebujna načina slikanja – tretman boja, pejsaža, stabala i samih likova seljaka, dok je sam sadržaj nadahnut legendom i snoviđenjima, karakterističan za njegove preokupacije tog razdoblja.

– Izvor: Ministarstvo kulture, Uprava za zaštitu kulturne baštine, 2011. - (EN) Ivan Generalić’s painting “The Unicorn” is a movable cultural monument by the decision of the Regional Institute for the Protection of Cultural Monuments in Zagreb, no. 02-748/1-74. from November 18, 1974, and registered in the Register of Movable Cultural Monuments of the Regional Institute for the protection of Cultural Monuments in Zagreb under the number RZG-138. It has the attribute of cultural property.

Painting “The Unicorn” by Ivan Generalic, oil on canvas, 76×145 cm, signed D.d. I.Gen. 1961, is one of the highest quality Generalić’s works from the 1960s, exceptional in terms of boldness in color due to the theme from folk tales. The work has all the characteristics of Generalić’s distinctive way of painting: the treatment of colors, landscapes, trees, and the very characters of the peasants, while the content itself is inspired by legends and dreams, characteristic of his preoccupations of that period.

– Source: Ministry of Culture, Directorate for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, 2011.

(HR) Djelo prikazuje staru legendu:

Samo jemput na leto, na Ivanjsku noč, i samo v jedno mesto, na Svetinjski breg zmed Sigeca i Hlebin, dojde Jednorog – bajoslovni beli stvor kak jelen ili viti konj z preštimanem rogom na čelu. On ki ga vidi more se pomladeti makar na jednu noč.

– Izvor: Vid Balog, Hrvatska bajoslovlja, Uriho, Zagreb, 2011.(EN) The painting tells a story about a very old legend:

Only once a year, in the midsummer night, and only at one place, the Holy Hill between Sigetec and Hlebine, the Unicorn appears, a fairy-tale white creature like a deer or a lean horse with an elegant horn on its forehead. The one who sees it can be rejuvenated, at least for one night.

– Source: Vid Balog, Hrvatska bajoslovlja, Uriho, Zagreb, 2011

- (HR) Trenutačno izloženo u Muzeju Grada Đurđevca

Preuzimanje: Prema dogovoru s kupcem - (EN) Currently exhibited in The Museum of the City of Đurđevac

Pick-up: According to agreement with the customer

Foto (Photo): Muzej Grada Đurđevca (The Museum of the City of Đurđevac), Ivan Brkić

- (HR) Published in

- (EN) Objavljeno u

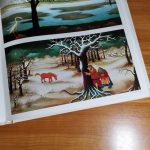

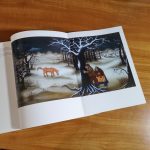

- Ivan Generalić – Spektar, Zagreb, 1973.

- Ivan Generalić – Spektar, Zagreb, 1973. – Rogati konj

- Ivan Generalić – Nebojša Tomašević, Italy, 1975.

- Ivan Generalić – Nebojša Tomašević, Italy, 1975. – Rogati konj

- Ivan Generalić – Hrvatski muzej naivne umjetnosti, Zagreb 2014.

- Ivan Generalić – Hrvatski muzej naivne umjetnosti, Zagreb 2014. – Rogati konj

- Putevima Hlebinske škole – Muzej grada Koprivnice, Koprivnica, 2018.

- Putevima Hlebinske škole – Muzej grada Koprivnice, Koprivnica, 2018. – Rogati konj

De Lusthof der Naieven, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam 1964; Le Monde des Naifs, Musee National d’Art Moderne, Paris 1964; Modra lasta, br. 11, Zagreb 1.2.1965; Boris Kelemen: Naivno slikarstvo Jugoslavije, Galerije grada Zagreba, Spektar, Stvarnost, Zagreb 1969, str. 37; 2. trienale insitneho umenia, Slovenska narodna galeria, Bratislava 1969; Nok Lapja, Budapest 26.12.1970; Glas Podravine, Koprivnica 4.6.1971, str. 11; Oto Bihalji Merin: lvan Generalić, katalog, Ilijanum, Šid 1972; Mića Bašičević, Anatole Jakovsky, Boris Kelemen: lvan Generalić, monografija, Zagreb 1973; Naivi “73 / Generalić, katalog retrospektivne izložbe, Galerija primitivne umjetnosti, Zagreb 1973; Grgo Gamulin: I Pittori Naifs della Scuola di Hlebine, Mondadori, Milano 1974; Večernji list, Zagreb 3.1.1976; Review, Beograd, lipanj 1976, str. 29; Nebojša Tomašević: Magični svet Ivana Generalića, Beograd 1976, str. 164-165; Boris Kelemen: Naive Art in Yugoslavia, Camden Arts Centre, London 1976, naslovnica; Boris Kelemen: Naive Art in Yugoslavia, katalog, Galerija primitivne umjetnosti, Zagreb i Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service, Washington D.C. 1976, naslovnica; The Milwaukee Journal, Milwaukee 30.1.1977; Boris Kelemen: Naivno slikarstvo u Jugoslaviji, Grafički zavod Hrvatske, Zagreb 1977; Selezione dal Reader’s Digest, Milano, srpanj 1980, str. 40; Marijan Špoljar i Tomislav Šola: Hlebinski krug / Pedeset godina naivnog slikarstva, Galerija primitivne umjetnosti, Zagreb i Muzej grada Koprivnice, Koprivnica 1981, str. 24; Primitive Painting, The Alpine Fine Arts Collection Ltd., New York i Spektar, Zagreb 1981, str. 198; Večernji list, Zagreb 13.3.1984, str. 5; Victor Ernest Masek: Arta Naiva, Editura Meridiane, Bucuresti 1989; Večernji list, Zagreb 7.12.1992, str. 29; Euro-city, br. 1, Zagreb 1995; Ratko Vince, Josip Depolo, Ivan Rogić Nehajev: Čudo hrvatske naive, Amalteja i HMNU, Zagreb 1996, str. 67; Radost, br. 7, Zagreb, ožujak 1997, str. 16; Thema / Encyclopedie Larousse / Arts et Culture, Larousse, Paris 1997, str. 297; The Fantastical World of Croatian Naive Art, katalog, Museum of Fine Arts, St. Petersburg, Florida 2000, str. 49; Da Rousseau a Ligabue / Naif?, Palazzo Bricherasio, Torino 2002, str. 130; Podravski zbornik, Muzej grada Koprivnice, Koprivnica 2005, str. 126; Vladimir Crnković: Umjetnost hlebinske škole, deplijan, HMNU, Zagreb 2005; Vladimir Crnković: Umjetnost Hlebinske škole, HMNU, Zagreb 2005, str. 69 (drugo izdanje 2006; treće izdanje 2012); Večernji list, Zagreb 31.5.2005, str. 48; Fokus, Zagreb 10.6.2005, str. 52; Croatia, Croatia Airlines, Zagreb, jesen 2005; Harada Talzi and Fellow Painters from Croatia, The Asahi Shimbun, Tokyo 2005, str. 72-73; Slobodna Dalmacija, Split 20.12.2009, str. 27; Hrvatska umjetnost / Povijest i spomenici, Institut za povijest umjetnosti i Školska knjiga, Zagreb 2010, str. 655

- (HR) [VIDEO] Ivan Generalić – Evo zašto je nastao Rogati konj (Hrvatski, s titlovima)

- (EN) [VIDEO] Ivan Generalić – The story behind the creation of The Unicorn (Croatian, English subs)

o

Ivan Generalić, “Moj unuk” (My grandson)

- Ivan Generalić, 1972, Moj unuk (My grandson), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 120×160 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

- (HR) Objavljeno u

- (EN) Published in

- Ivan Generalić – Spektar, Zagreb, 1973.

- Ivan Generalić – Spektar, Zagreb, 1973. – Moj unuk

o

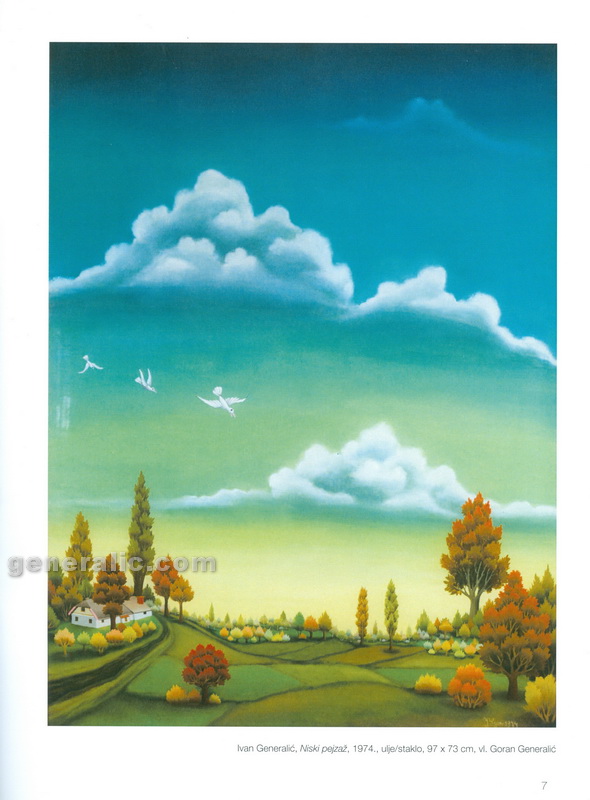

Ivan Generalić, “Niski pejzaž” (Low landscape)

- Ivan Generalić, 1974, Niski pejzaž (Low landscape), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 97×73 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

o

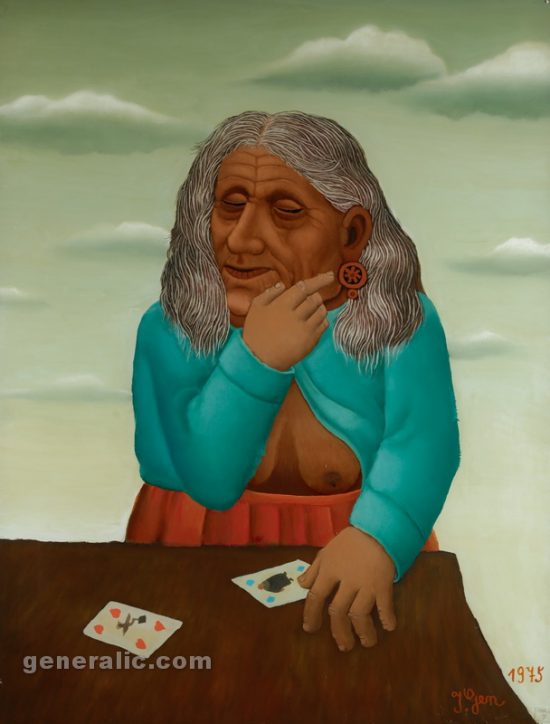

Ivan Generalić, “Gatara” (Divination)

- Ivan Generalić, 1975, Gatara (Divination), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 97×75 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

|

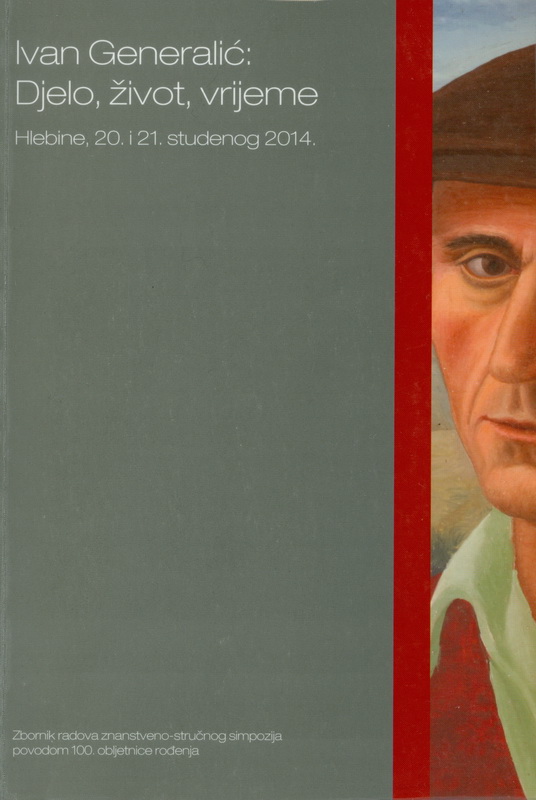

(HR) … Gatanju se Ivan Generalić vraća u slici Gatanje iz 1975., gdje je gledatelj osobno suočen s gatarom – sada je on umjesto žene za stolom i više nije promatrač žanr-prikaza, nego sam postaje dio radnje. No, najintrigantniji detalj je lice gatare. Uspoređujući fizionomiju Generalićevog lica s fotografijama iz tog razdoblja i naslikane Ciganke, moguće je postaviti tezu da je Generalić sam sebe naslikao kao Ciganku razdrljenih ženskih grudi… … Ovo je najtajanstvenija od svih Generalićevih slika i vjerojatno jedna od najintimnijih. Zašto Ciganka pokazuje na svoju naušnicu u obliku kotača? To je simbol romskog naroda—hinduistička čakra, kotač života. No koristi li ga Generalić kao simbol kršćanskog kotača života? Govori li stol s kartama da se upravo gata naša sudbina, sudbina promatrača? Ili je ovo intimno zrcalo koje je Generalić postavio samome sebi? …. … Koja je simbolika karata? Jesu li to dva asa – as života i smrti? Na jednoj karti roda nosi dijete, simbol novog kruga života, dok je na drugoj svećenik koji daje posljednju pomast. A zašto je Ciganka nasmiješena? Je li taj tajanstveni osmijeh preuzet s nekog drugog portreta? Je li ovo Generalićeva ciganska Mona Lisa? … – Antonio Grgić, “Ivan Generalić: Djelo, život, vrijeme.” Hlebine, studeni 2014. Zbornik radova znanstveno-stručnog simpozija u povodu 100. obljetnice rođenja. Izvadak. |

(EN) … Generalić returns to the theme of fortune-telling in the 1975 painting “Divination” where the viewer is personally confronted by the fortune teller—this time, the viewer has taken the place of the woman at the table and is no longer a passive observer of a genre scene, but instead becomes part of the narrative. However, the most intriguing detail is the face of the fortune teller. Comparing Generalić’s facial features with photographs from that period and with those of the painted Roma woman, one can put forth the theory that Generalić painted himself as the Roma woman, bare-chested… … This is the most enigmatic of all Generalić’s paintings and likely one of his most intimate. Why is the Roma woman pointing to her earring shaped like a wheel? It is a symbol of the Roma people—the Hindu chakra, the wheel of life. But is Generalić using it as a symbol of the Christian wheel of life? Does the table with the cards suggest that our fate—the viewer’s fate—is being foretold? Or is this an intimate mirror that Generalić set up for himself? … … What is the symbolism of the cards? Are they two aces—ace of life and ace of death? On one card, a stork carries a child, symbolizing a new cycle of life, while on the other, a priest delivers the last rites. And why is the Roma woman smiling? Is that mysterious smile borrowed from another portrait? Is this Generalić’s Roma Mona Lisa? … – Antonio Grgić, “Ivan Generalić: Work, Life, Time.” Hlebine, November 2014. Proceedings of the Scientific and Expert Symposium marking the 100th anniversary of his birth. Excerpt. |

o

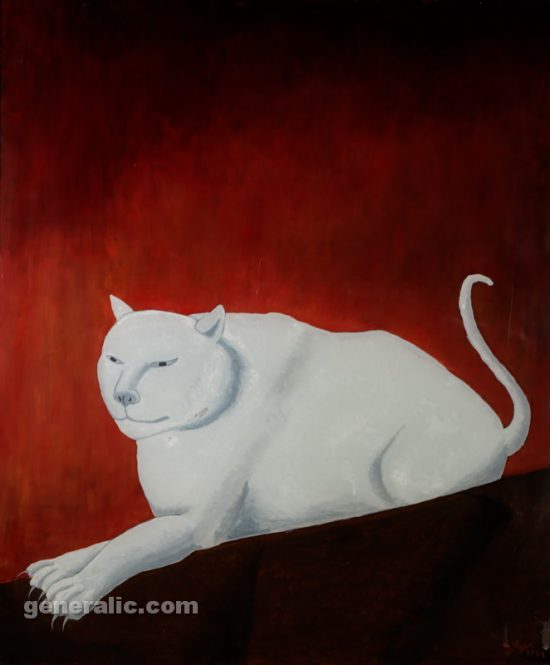

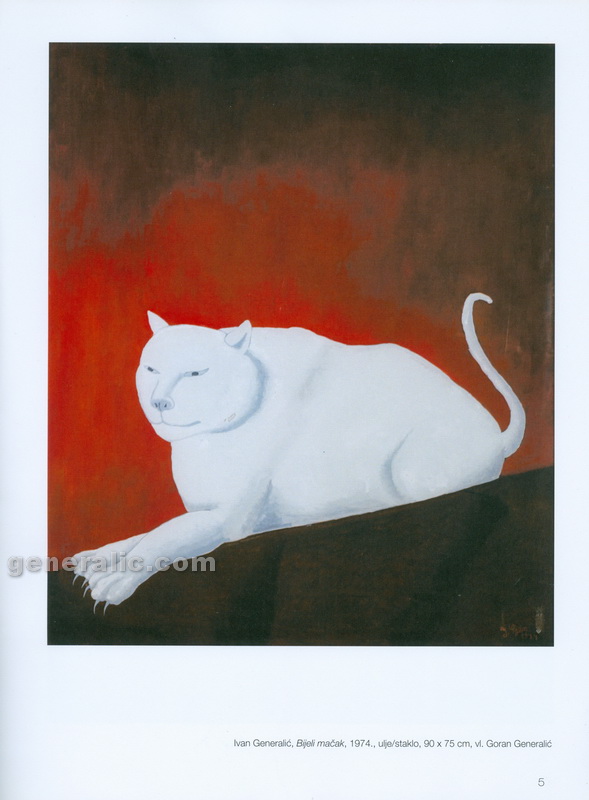

Ivan Generalić, “Bijeli mačak” (White cat)

- Ivan Generalić, 1974, Bijeli mačak (White cat), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 90×75 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

- (HR) Napomena: Oštećena boja na vratu i obrazu.

- (EN) Note: Damaged paint on cat’s neck and cheek

o

Ivan Generalić, “Som” (Catfish)

- Ivan Generalić, 1992, Som (Catfish), pastel na papiru (pastel on paper), 50×36 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

- (HR) Som koji lovi udah zraka je vjerojatno posljednje djelo Ivana Generalića.

- (EN) Catfish gasping for air is possibly the last painting made by Ivan Generalic.

o

Josip Generalić, “Berba grožđa” (Vintage)

- Josip Generalić, 1973, Berba grožđa (Vintage), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 100×170 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

- (HR) Objavljeno u

- (EN) Published in

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988.

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988. – Berba

o

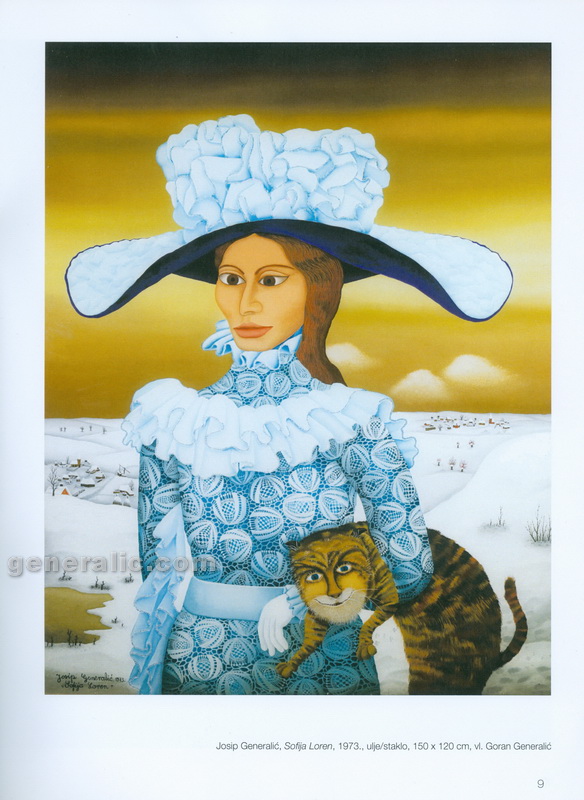

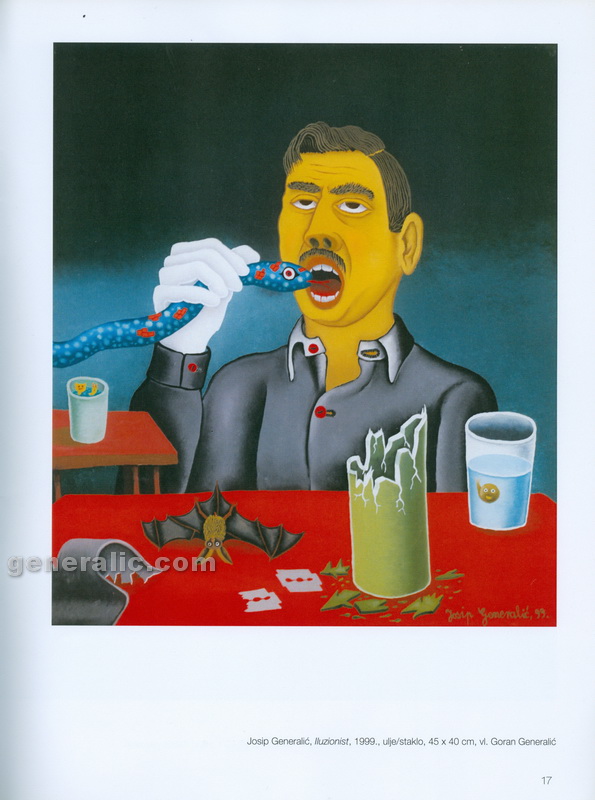

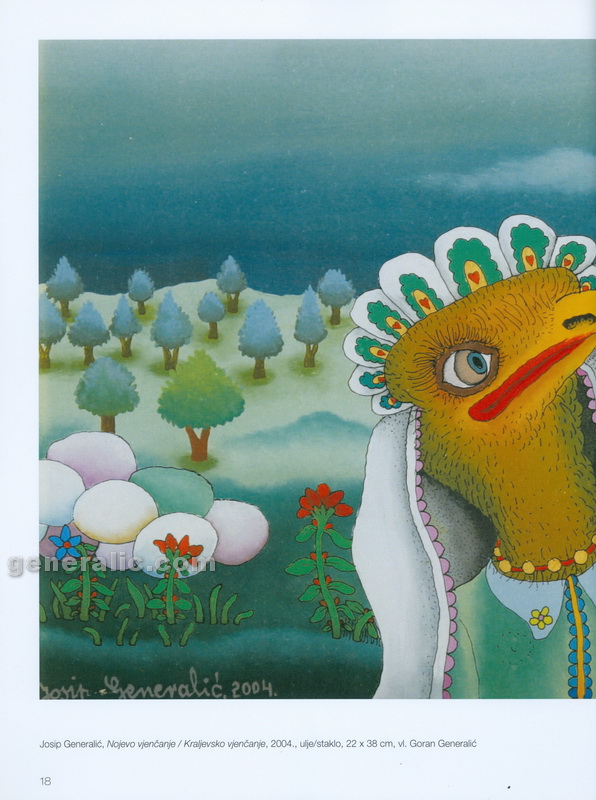

Josip Generalić, “Sofija Loren” (Sophia Loren)

- Josip Generalić, 1973, Sofija Loren (Sophia Loren), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 150×120 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

|

(HR) Slika prikazuje poznatu talijansku glumicu Sofiju Loren u bogato ukrašenoj plavoj haljini i šeširu, smještenu u snježni podravski pejzaž. U njenom naručju nalazi se tigrasti mačak, za kojeg je Generalić šaljivo izjavio da simbolizira njezinog supruga, aludirajući na ideju da žene drže muškarce “pod kontrolom.”

|

(EN) The painting depicts the famous Italian actress Sophia Loren dressed in an ornately decorated blue gown and hat, set against a snowy Podravina landscape. In her arms rests a tabby cat, which Generalić humorously claimed symbolizes her husband – suggesting, with a touch of irony, that women keep men “under control.”

|

- (HR) Objavljeno u

- (EN) Published in

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988.

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988. – Sofija Loren

o

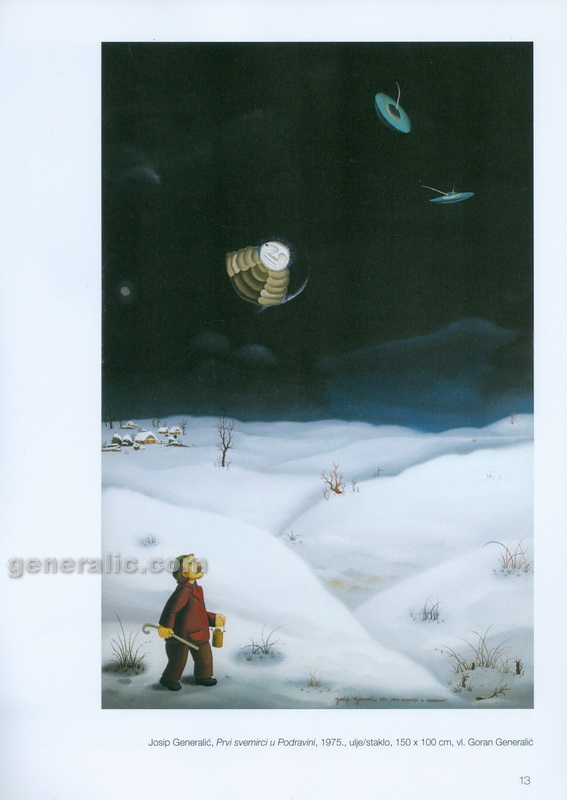

Josip Generalić, “Prvi svemirci u Podravini” (First aliens in Podravina)

- Josip Generalić, 1975, Prvi svemirci u Podravini (First aliens in Podravina), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 150×100 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

|

(HR) … Sposobnost slikara da određene pojave i ličnosti asimilira u nove prostore i da ih na neki način “naturalizira”, dobit će i u ovom slučaju novu potvrdu. Kompozicija koja ima naslov Jerihonski anđeo, a predstavlja astronauta što se sa svemirske letjelice spušta u tipičan zimski podravski pejsaž, najavljuje novi odnos prema tom motivu. Još eklatantniji primjer bit će staklo Svemirci u Podravini, gdje je već takoreći došlo do “susreta treće vrste”. Autor međutim u tom uspostavljanju veze između Svemira i Hlebina ide još i dalje, pa na jednom od ostvarenja predstavlja kako “Imbro z Hlebin kolonizira Mjesec”… – Jugoart, 1988. Juraj Baldani. |

(EN) … The painter’s ability to assimilate certain phenomena and personalities into new spaces and, in a way, ‘naturalize’ them, will once again be confirmed in this case. The composition titled The Angel of Jericho, depicting an astronaut descending from a spacecraft into a typical winter landscape of Podravina, signals a new approach to this motif. An even more striking example is the glass piece Aliens in Podravina, where there has practically been a ‘close encounter of the third kind’. The artist, however, goes even further in establishing a connection between the Universe and Hlebine, and in one of the works depicts how ‘Imbro from Hlebine colonizes the Moon’… – Jugoart, 1988. Juraj Baldani. |

- (HR) Objavljeno u

- (EN) Published in

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988.

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988. – Prvi svemirci

o

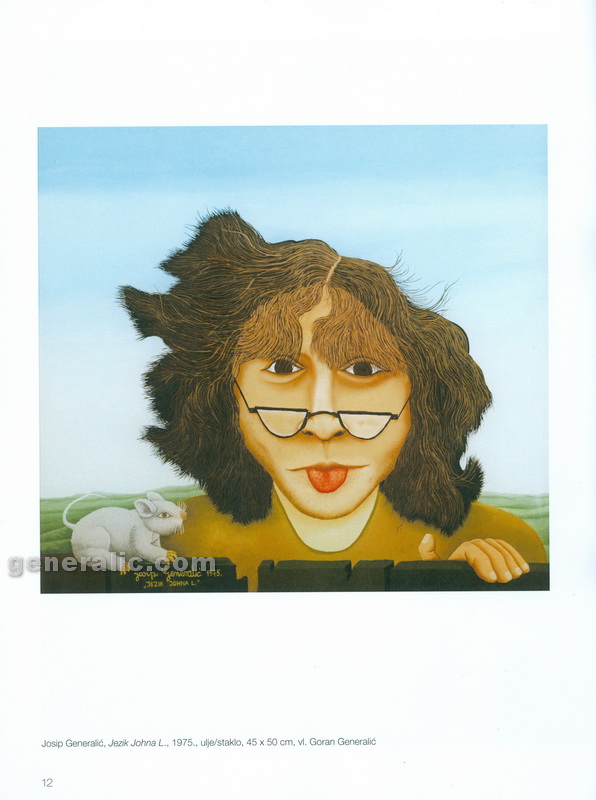

Josip Generalić, “Jezik Johna L” (John Lennon’s tongue)

- Josip Generalić, 1975, Jezik Johna L (John Lennon’s tongue), ulje na staklu (oil on glass), 45×50 cm – Cijena na upit (Price on request)

|

(HR) … Započeti ciklus portreta osoba iz showbusinessa Josip Generalić će uspješno nastaviti i u 1975. godini. Izdvajaju se tri ostvarenja: Jezik Johna L., Ringo S. z trubom i Janis Joplin s mikrofonom. Kao i kod predhodnih slučajeva, kulisa, odnosno pozadina, opet je podravski pejsaž, ali tek u blagim naznakama. Autor se koncentrirao na psihološki izraz modela nastojeći da izvjesnim karikaturalnim akcentima potencira individualnosti… – Jugoart, 1988. Juraj Baldani. |

(EN) …Josip Generalić would successfully continue the portrait cycle of show business personalities into the year 1975. Three works stand out: The Tongue of John L., Ringo S. with a Trumpet, and Janis Joplin with a Microphone. As in previous cases, the backdrop is once again the Podravina landscape, though only hinted at faintly. The artist focused on the psychological expression of the models, aiming to emphasize their individual traits through certain caricature-like accents… – Jugoart, 1988. Juraj Baldani. |

- (HR) Objavljeno u

- (EN) Published in

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988.

- Josip Generalić – Jugoart 1988. – Jezik Johna L.

o

- (HR) [VIDEO] Izložba kapitalnih djela u Galeriji Hlebine, svibanj 2018. (Hrvatski, bez titlova)

- (EN) [VIDEO] Exhibition of capital masterpieces in Gallery Hlebine, May 2018 (Croatian only, no subs)

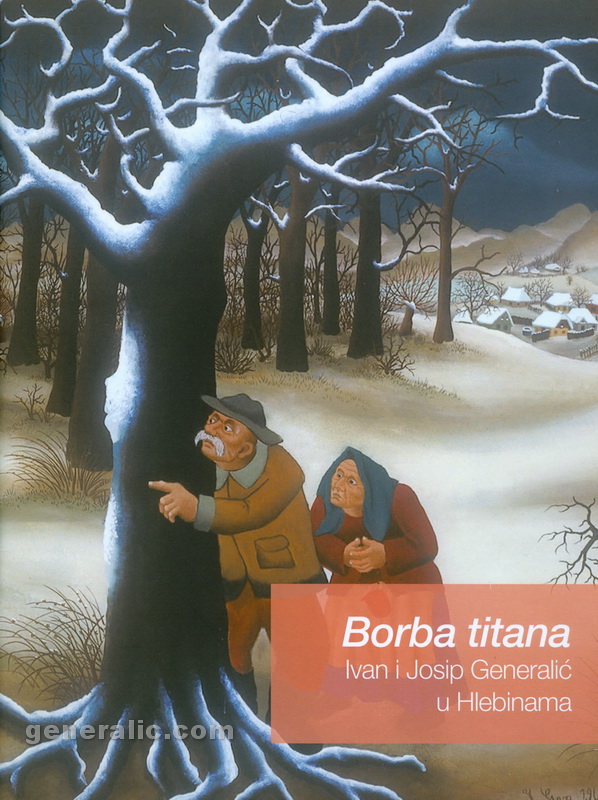

- (HR) Katalog izložbe

- (EN) Exhibition catalogue